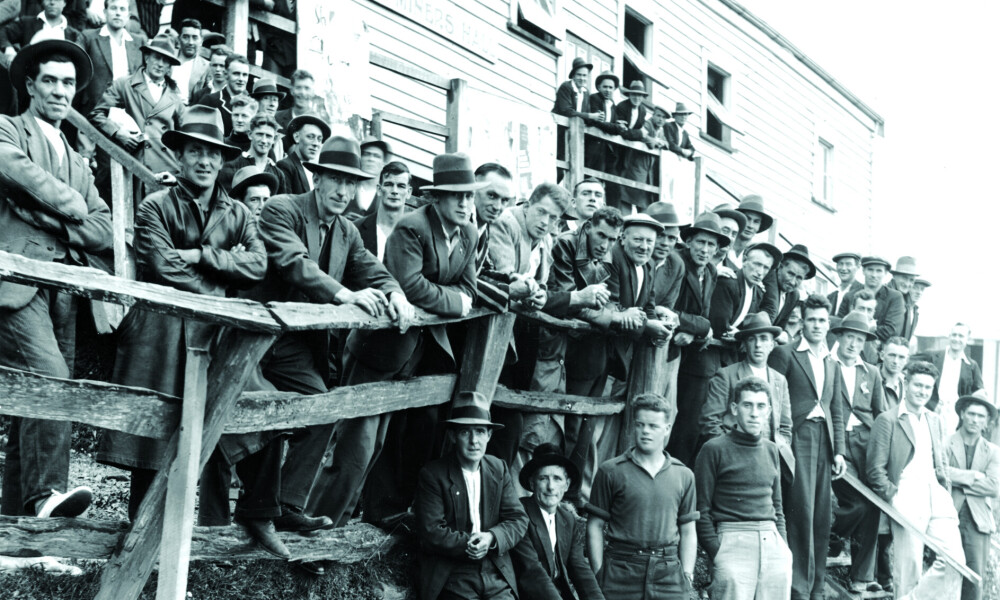

When you’re busy changing the world, keeping records isn’t always a top priority. Yet documenting the heritage of working-class struggle is hugely important.

Archives have power. They shape our understanding of ourselves as individuals, groups, and societies. They allow us to marshal stories and summon meaning.

That’s why the job of preserving labour history can’t be left to chance. The Alexander Turnbull Library – part of the National Library of New Zealand – recognised this early on.

AOTEAROA’S LOST LABOURS

The library recently published an online labour history guide, containing the official archives of workers’ organisations across various industries, including interviews, cartoons, ephemera, photography and more.

This was possible thanks – in large part – to the generosity of unionists, librarians and activists of decades past who donated to the library over the course of many years.

REMEDY FOR PRESENT EVILS

The archives include records of the PSA – which take up a whopping 333 boxes or 111.04 metres of shelving.

The PSA records, which date back to 1890, include photographs, letter books, cartoons, and manuscripts covering membership, industrial disputes, awards and agreements, workplace conditions, conferences, and branch and executive meeting minutes.

As the PSA’s general secretary wrote in 1981, the material spans a century and contains “material of

considerable historical interest.”

The Herbert Roth papers are particularly significant. A librarian and historian whose books include Remedy for Present Evils, a history of the PSA written in 1987, Roth was an avid collector of union and activist papers from union officials, shopfloor activists, and pioneering feminist organisers.

SLICE OF WORKING LIFE

Evidence of everyday working life is here, too. The Te Whaiti Family Papers (1870-1980) describe farming, family and Māori life in the Wairarapa, while Margaret Benton’s reminiscences (1881-1966) recall her working life as a domestic servant.

My personal favourite is the diary of itinerant labourer James Cox. From at least 1888 onwards, this swagman scrawled daily entries about his struggle to make a living onto tiny pieces of paper. By 1925, this remarkable account amounted to almost 8,000 pages and 800,000 words.

They have inspired books, blogs and even a Twitter account @cox_diary

PSA JOURNAL ARCHIVE

It’s not all manuscripts. The guide has links to hundreds of interviews, thousands of cartoons, and hundreds of thousands of photographs. There’s a section for newspapers, journals and books, including the PSA Journal’s own online archive.

Whether you’re exploring the past, or drawing links to the present, the labour history guide is wonderful place to start.

Nā Jared Davidson, research librarian at the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington.